Has a Nobel Laureate Become a War Criminal?

Starving civilians as a weapon of warfare is prohibited under UN Security Council Resolution 2417, and is recognised as a war crime.

So, what is a Nobel Peace Prize winner who does just that?

And what are the governments who sell him weapons?

The current war in Ethiopia’s Tigray region begs an answer to both those questions.

Under the headline “Steal, Burn, Rape, Kill”, Alex de Waal, executive director of the World Peace Foundation, noted that even as the Ethiopian and Eritrean governments are shopping for drones and other sophisticated armaments, “for now their most reliable weapon is hunger: they aim to starve Tigray into submission and keep it permanently dependent on an international aid pipeline that they can switch on and of at will.” (London Review of Books 17 June 2021)

As for switching off the flow of weapons — in the arms bazaars of China, Bulgaria, Israel, Ukraine and others, the only concern is: “How much can you pay?”

And while they’re filling their shopping carts, Ethiopian forces driven back by the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) have cut electricity lines and destroyed two bridges that are key for the delivery of aid.

It’s not as if the world can say “we didn’t see it coming”.

In his 1988 book “Surrender or Starve: The Wars Behind the Famines”, renowned political and travel writer Robert Kaplan noted that to a significant degree the mid-1980s famine in the Horn of Africa was “a manipulated consequence of war and ethnic strife”.

(FULL DISCLOSURE: Robert Kaplan has been a friend for nearly 40 years, and quotes me in the book)

STARVATION AND A PRIZE LIE

Today, more than three decades later, the U.S. and aid agencies estimate that as many as a million people are starving again in Tigray.

Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, the 2019 Nobel Peace Prize winner, insists there is “no hunger” there.

The prime minister’s bald-faced lie would be laughable were it not so wicked. Determining the exact scale of the starvation is impossible under the circumstances, but history and available evidence make the number of victims more than credible.

NO STRANGERS TO CONFLICT

War is part of the warp and weave of Tigray.

In “The Blue Nile”, author Alan Moorhead noted that when the Scottish explorer James Bruce visited the area in 1770, there were “endless marchings and counter-marchings of futile little armies”.

Tigrayans rebelled against Emperor Haile Selassie in the 1940s. In the mid-1970s the TPLF launched a guerrilla war against the brutal Derg regime that had ousted the emperor. By 1991 the TPLF was in the capital, Addis Ababa.

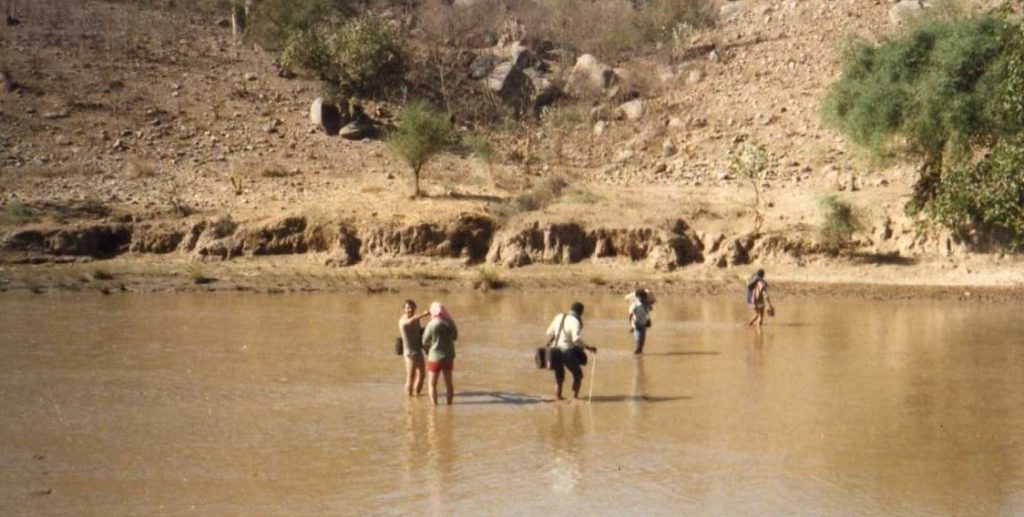

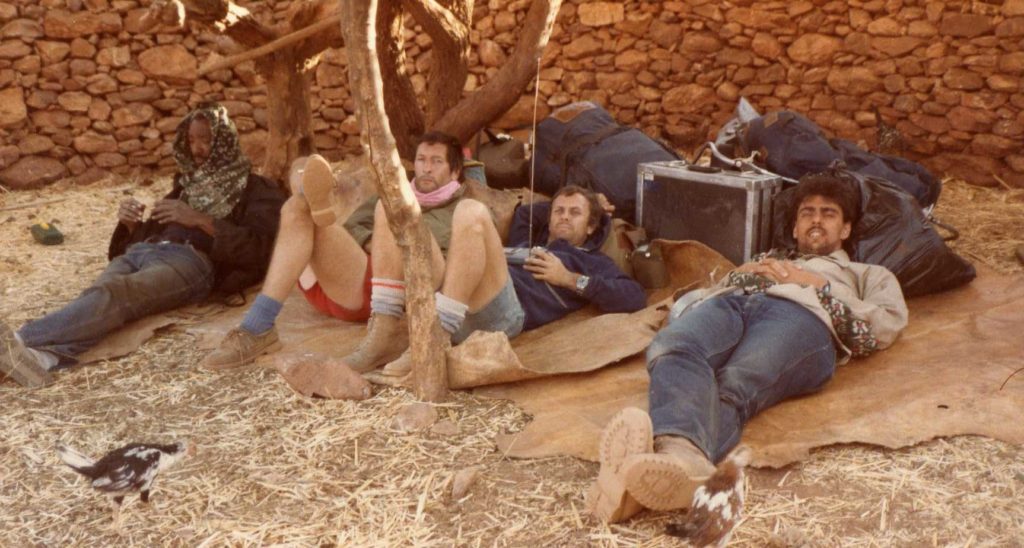

In 1985 three colleagues and I spent nearly a month traveling with the TPLF.

By definition, that makes maintaining objectivity, sorting wheat from chaff in the information given and what you get to see and videotape a challenge.

But acute hunger and the ravages of war are just plain obvious. So were the Ethiopian air force jets that prowled overhead.

A LAND OF RAVAGED BEAUTY

The landscape we traveled through was spectacular, and brutal.

Brown, dust-dry terraced hillsides were bereft of crops, or any potential to grow them until the drought broke and the war stopped. Villages lay in ruin, many of them abandoned by people who’d had no option but to walk away in hope of finding food aid.

It was a sad fate for the legendary birthplace of Ethiopia’s first emperor, Menelik I, the son of the Hebrew King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba.

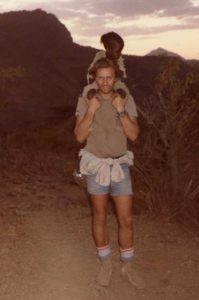

At one point we came upon a family of five struggling down a steep cliffside path.

The father was burdened with a bundle of possessions, and leading a small boy by the hand.

His wife had a baby on her back and bundles in each hand.

A little girl in a ragged dress struggled to keep up.

By the time we reached the bottom, my legs told me hoisting her onto my shoulders had been a bad idea.

The family’s shy smiles told me otherwise.

Three weeks of travel across Tigray led me to report that the Ethiopian government’s “only contribution to hunger is bombs.” And so it remains today.

NO ABSOLUTE GOOD GUYS

And lest it seem the TPLF are angels, twenty-five years after our trip to Tigray, it was discovered that millions of dollars handed over to them to buy food, was diverted to purchase weapons. In hindsight, it might have occurred to me that the TPLF was too good to be true.

On the other hand, I think the aspects of their operations that we saw, including clinics and food distribution, were a genuine reflection of their positive side. And I doubt the people we traveled with knew what was being done higher up their organisation.

Unless the outside world steps in, stops the flow of weapons and insists on unhindered access for aid agencies, the people of Tigray are right back where they were in the 1980s.

And for the Prize liar and the arms suppliers, it looks very much like “business as usual”.

Comments are welcomed, Just click CONTACT

To receive new post alerts, click SUBSCRIBE